Entrevista a Chris Ainsley, creador de Adventuron Classroom

·Una figura clave en la ficción interactiva moderna

Jump to the english version of the interview

Hace unos meses me animé a participar en un par de jams organizadas en itch.io. En una de ellas presenté “The Mansion”, una aventura conversacional muy sencilla que no fue precisamente de las primeras en el ranking, pero que me permitió dos cosas. La primera fue ganar una copia de “Hibernated I: This place is death” en formato físico gracias a la generosidad de Stefan Vogt (y un poco de suerte). La segunda fue conocer una comunidad fantástica de aficionados a las aventuras conversacionales.

El organizador de la jam era Chris Ainsley, el creador de la intuitiva herramienta Adventuron Classroom que tenía que usarse en la competición, y que ha servido para la creación de multitud de aventuras basadas en navegador web. Cuando Chris pidió ayuda para traducir “Two” al castellano no dudé en echarle una mano, y finalmente el resultado acabó publicándose hace algo más de un mes. En las conversaciones que tuvimos le pregunté si se animaba a responder a algunas preguntas sobre Adventuron y el mundo de las aventuras en general, y el resultado lo podéis leer a continuación.

Entrevista traducida al castellano

Mark James Hardisty publicó un artículo sobre ti en el quinto número de The Classic Adventurer y comentabas que creaste Adventuron para ver si era factible crear un IDE complejo en un navegador web. Después de todo este tiempo, ¿crees que ha cumplido tu propósito inicial o quizás tiene que evolucionar un poco más?

Estoy trabajando en varios aspectos del editor para hacer las cosas mucho más agradables. Nunca va a ser un IDE complejo, pero creo que cumple en gran medida las características mínimas que se pueden exigir a un producto de este tipo.

El año pasado el proyecto se convirtió en Adventuron Classroom, una herramienta “diseñada para enseñar a niños de ocho y más años a programar y a aprovechar sus habilidades naturales para crear historias”. ¿Cuántas escuelas se han puesto en contacto contigo para usar Adventuron Classroom como herramienta educativa?

Me he puesto en contacto con muchos colegios, incluido al que fui de pequeño, y también con muchos profesores pero creo que, tal y como están las cosas, no ha conseguido atraer al público objetivo.

También me puse en contacto con la biblioteca local para ver si podía organizar una sesión de “aprende a programar” pero me dijeron: “creemos que el aspecto retro podría ser interesante para adultos que recuerdan como solía ser la informática clásica, pero viendo los gráficos de los juegos de hoy en día a los niños les parecería muy anticuado”.

No se puede ir en contra de un consenso abrumador.

Mi próximo objetivo es añadir un editor gráfico y mejorar la interfaz de usuario para minimizar el uso de código en las primeras fases del desarrollo.

Los juegos creados con Adventuron no solo se pueden jugar en navegadores (tanto en escritorio como en dispositivos móviles), sino que has creado utilidades para que el código pueda usarse en parsers como PAW o DAAD. ¿Qué te motivó a hacer esos conversores?

Nunca quise que Adventuron fuese una plataforma para hacer conversiones, quería que se usase para crear contenido original. Creo que me consentí un poco a mi mismo porque hacer ese tipo de utilidades es divertido.

Has creado tu propia herramienta para crear muchas aventuras, incluyendo adaptaciones de juegos clásicos. ¿Cuál ha sido el más divertido de crear? ¿Y el más popular?

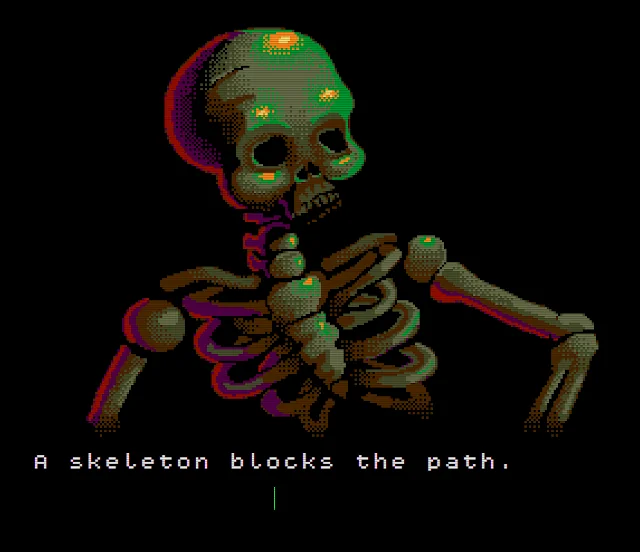

“THE PATH” es el juego más jugado de los que he publicado hasta ahora. Tiene más de 6000 visitas en la página (el número de veces que se juega no se registra actualmente de forma precisa en itch.io).

“THE PATH” es un puzle basado en objetos con un par de giros inesperados. Quería crear un juego que alguien que no conociese las convenciones de las aventuras conversacionales pudiese jugar. Sabía que quería hacer una aventura sin las opciones de movimiento habituales en este tipo de juegos.

También me di cuenta de que la mayoría de las aventuras de texto se basan en la búsqueda de sustantivos, a base de

EXAMINAR XXX, y luego averiguar qué hacer con esos objetos. ¿Y si el rompecabezas fuese puramente saber qué usar en cada momento? ¿Qué pasaría si usas el objeto incorrecto en el lugar equivocado? Eliminé la navegación así como la obtención de objetos y lo único que debe hacer el jugador es pensar cómo usar lo que tiene en el inventario.El juego (parece) muy simple. Al jugador se le muestra una situación con una frase, y debe decir al juego qué objeto usar para solucionar el problema. Una vez que se usa el objeto se pierde, y se muestra otro escenario.

Hay doce en total y se muestran en un orden pseudoaleatorio. Esto se hace de forma intencionada, para forzar al jugador que no memorice y que ajuste su camino usando una variable cada vez.

Si el camino está desordenado, el jugador debe recordar lo que ha aprendido en cada paso en vez de repetir mecanicamente las mismas acciones, algo que creo que terminaría siendo algo tedioso, como escribir una lista.

“THE PATH” juega un poco con la mente del jugador, y puede ocasionar frustración extrema, obsesión o te puede encantar. Como el juego fue lanzado de forma gratuita y experimental, no me importó que los jugadores pensasen que el juego era injusto. La alternativa habría sido estropear las revelaciones que tienen que venir solas al jugar.

Perder y ganar sabiduría en el proceso es la mecánica central del juego. Es extremadamente improbable que alguien se pase la aventura en su primera partida.

Y el último es “TWO”, un juego también corto y sin historia…

Desarrollar “TWO” fue un placer porque lo escribí muy rápido y me encantó el desafío de hacer un juego en el que todos los mensajes tenían un máximo de dos palabras (nota del traductor: en español ese desafío fue incluso mayor 8-) ).

Los que me conocen saben que me da especial tirria cuando se emplea mal la expresión “ficción interactiva” como sinónimo de “aventuras conversacionales”, ya que no se puede usar para aquellas que se basan principalmente en la manipulación de objetos.

Siento que es un obstáculo cuando insistes en definir un género con una palabra ("ficción") que no se aplica universalmente a todos los juegos de ese tipo.

En cualquier caso, teniendo en cuenta el límite de las dos palabras, “TWO” tenía que ser forzosamente un juego basado en puzles. Creo que los juegos que se basan principalmente en puzles son divertidos, pero solo es mi opinión 😄

El hecho de que “TWO” no tuviese historia fue algo deliberado. No tiene más narrativa que un juego de plataformas en dos dimensiones. Y sin embargo, en itch, tuve que elegir la categoría “ficción interactiva”. Los que controlan haciendo lo suyo.

Por curiosidad, ¿cuáles son tus aventuras conversacionales favoritas en los ochenta?

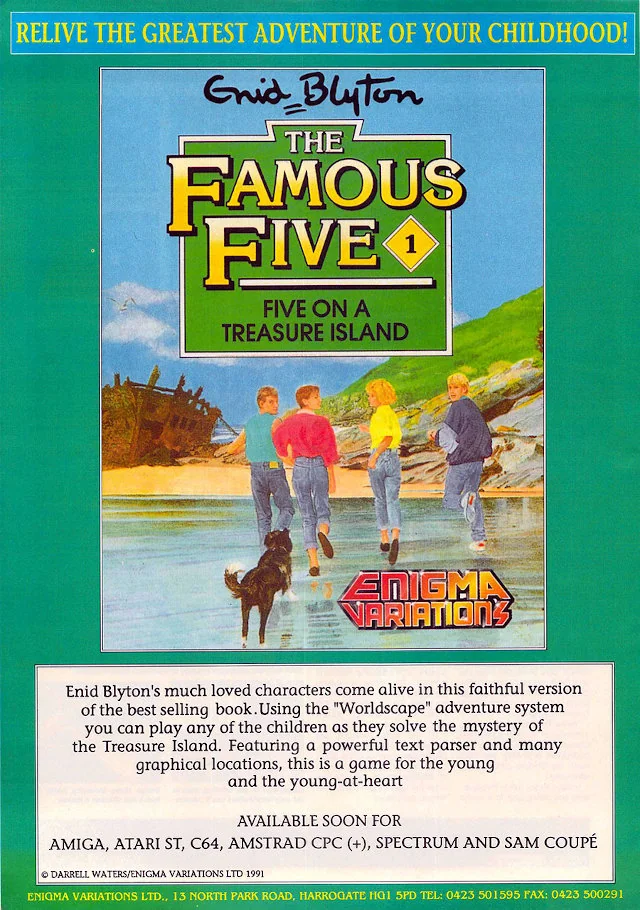

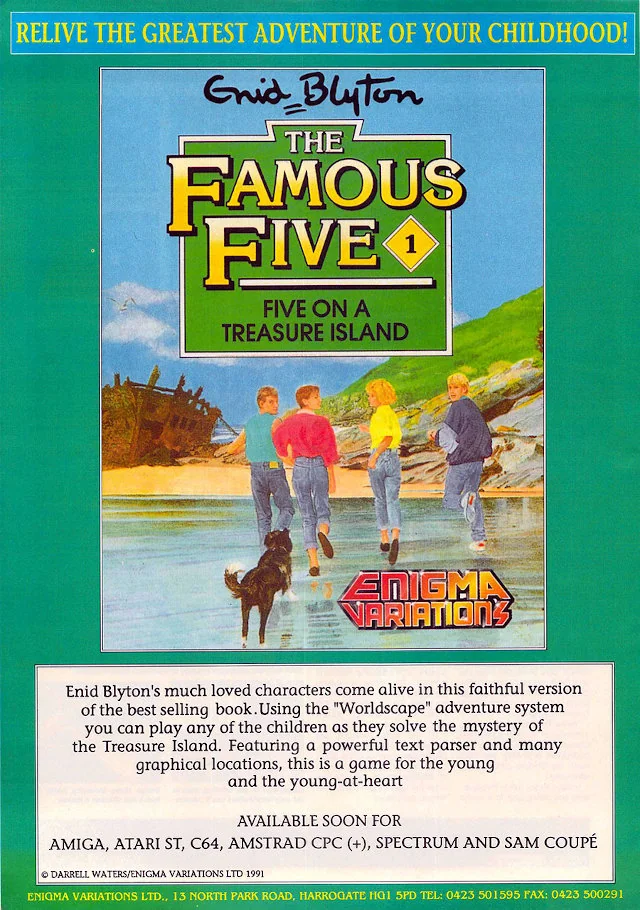

Personalmente ADORO “The Famous Five”. También me gustan “Robin of Sherwood”, “Rebel Planet”, “Gremlins”, y otros similares. ¡Ah!, “Valkyrie 17” fue un placer culpable también. Recuerdo que lo compré en un mercadillo situado en Covent Garden.

Más tarde me empezaron a gustar aventuras con más texto y menos gráficos, como “The Beast”.

En aquel entonces, desarrollar para los primeros ordenadores domésticos era muy diferente a cómo se trabaja hoy en día. ¿Crees que hacer software ahora es una experiencia mejor gracias a los IDEs y webs como Stack Overflow? ¿O quizás los desarrolladores eran más creativos hace décadas cuando los recursos eran más limitados en todos los sentidos?

¿El desarrollo actual es mejor? Bueno, creo que depende de cada uno. No hay nada perfecto.

Creo que mucha gente que quiere hacer una aventura con estilo ocho bits no quiere solamente quedarse ahí. Quieren hacer una aventura en sistemas de ocho bits y eso implica pagar el precio que sea necesario para conseguirlo.

Las herramientas para hacer aventuras de ocho bits DE VERDAD (en contra de la aproximación que supone Adventuron) cada vez son mejores.

Sin embargo, tienes que lidiar con muchos problemas como el espacio en pantalla, la velocidad al cargar gráficos, la memoria, la distribución, el hecho de que recuperar la partida guardada no es algo tan rápido, o la incapacidad para escalar al perfil del dispositivo. Pero, por otro lado, se siente como algo auténtico, y es una pasada ver tu aventura de estilo clásico en hardware real (lo siento Adventuron).

Para aquellos que no exijan una experiencia nostálgica tan pura, el objetivo de Adventuron es ofrecer un ciclo de desarrollo realmente rápido. Cuando cambias algo lo puedes probar inmediatamente y ver si funciona. No hay que instalar nada, solo acceder a la URL.

Adventuron es mucho menos eficiente que los parsers clásicos. Consigue emular su funcionamiento, pero la flexibilidad tiene su precio en bytes. Esa es otra razón por la que me encantan los conversroes. Puedo decir que un juego creado en Adventuron funciona en un Spectrum (al menos técnicamente hablando).

Como he dicho antes, los juegos creados con Adventuron se pueden disfrutar en navegadores de escritorio y en dispositivos móviles. Sin embargo, creo que hacerlo en un móvil o incluso en una tablet no es tan satisfactorio como hacerlo en un ordendor con su teclado. ¿Crees que esto supone un problema para atraer a nuevos jugadores o es más problemático el hecho de que la gente cada vez quiere leer menos al jugar?

Creo que depende del estilo de juego, la forma en la que muestra el texto, la calidad de los atajos y cómo de bien se juega y se siente en el móvil.

Creo que un juego como “TWO” realmente se disfruta más en un móvil. Tienes feedback háptico al pulsar en la pantalla y los comandos son cortos. El texto siempre cabe en la pantalla y las letras son grandes (25 columnas). Además puedes moverte al pulsar las direcciones, algo que resulta extrañamente satisfactorio.

En juegos con mucho texto, un parser complejo y mucha búsqueda de sustantivos, creo que jugar en móvil puede ser agotador.

Adventuron poporciona a los autores herramientas para optimizar cómo se visualizan los juegos en móviles. Eso implica asegurarse que los gráficos están en formato apaisado (al menos 3:1), no mostrar listas verticales de objetos, e integrar la descripción de la localización en el texto principal en vez de usar otra línea.

También hay que optimizar los espacios en blanco y asegurarse de que las partes largas de la narrativa se muestran cada una en un párrafo.

Las versiones posteriores se Adventuron tendrán mejor gestión del scroll y ofrecerán más opciones de escalado del texto. Adventuron puede ser divertido de usar con el juego adecuado, pero hay mucho margen de mejora a nivel de sistema para juegos que tengan mucho texto.

Hace ocho años Andrew Plotkin me comentó que había implementado funcionalidades como mapas dinámicos o toma de notas para ayudar a los jugadores. ¿Has pensado incorporar este tipo de mejoras en Adventuron Classroom o prefieres centrarte en mejorar el parser en sí?

Creo firmemente que la navegación es un problema importante para los que empiezan en este género, e incluso para jugadores experimentados en mapas grandes, así que he estado desarrollando un sistema de automapa y transporte, que debería publicarse a lo largo de este 2020.

Es un sistema basado en rejilla y utiliza los datos del juego y las áreas que ya se han explorado para mostrar el mapa de forma dinámica.

Creo que las ayudas visuales te sacan un poco del juego, pero también es cierto que ofreciendo distintas formas de configuración puedes conseguir agradar a todo el mundo.

Por supuesto, la toma de notas dentro del juego también es una meta personal, y también la posibilidad de poder jugar sin teclado (algo que mostré a algunas personas en la pasada Play Expo).

Has organizado recientemente algunas jams en Itch.io que han originado la creación de muchas aventuras nuevas. Una de ellas ("Mushroom Hunt") incluso apareció comentada en Rock, Paper, Shotgun. ¿Estás contento con la respuesta de la comunidad?

Estoy muy contento con la respuesta que han tenido las jams. Creo que es mucho más divertido crear algo en un entorno social y también de forma pseudo-competitiva.

La primera Adventuron CaveJam fue más popular de lo que me esperaba, y creo que la clave fue proporcionar una plantilla sobre la que trabajar y unas reglas muy sencillas para participar.

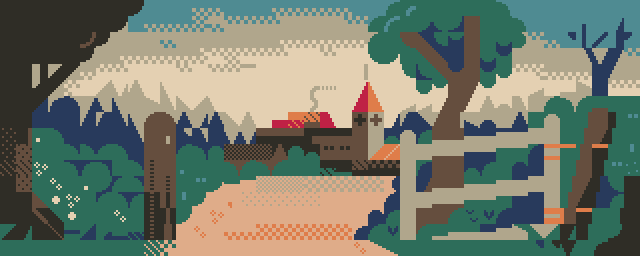

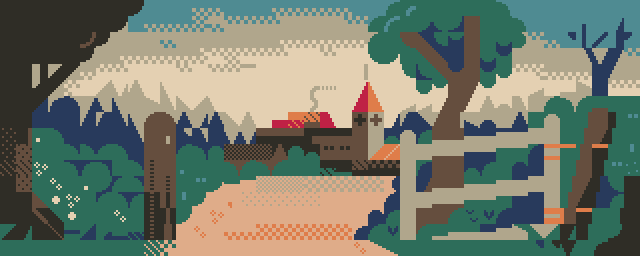

“Mushroom Hunt” fue el gran éxito de la primera jam. Es precioso y atrajo muchas miradas por méritos propios pero hubo otras obras destacables también. No quiero centrarme en otros juegos porque no quiero mostrar favoritismos, pero estoy muy contento con la calidad de algunos juegos.

La Halloween Jam vino poco después y se presentaron algunos juegos realmente increíbles. También me ha encantado ver como hay gente que se ha animado a programar por primera vez y aún así han conseguido crear juegos muy bien escritos y con un gran diseño en estas dos competiciones.

He estado empleando mi tiempo en mis otros proyectos, así que de momento voy a dejar de organizar este tipo de eventos hasta que termine de implementar nuevas funcionalidades en Adventuron y tenga más tiempo libre. Creo que volver a hacer lo mismo es aburrido para mi y también para la gente que participa. Prefiero darle una vuelta al tema.

Has vivido recientemente en Japón, un país en el que se ha publicado una gran cantidad de aventuras de texto. Algunas de ellas son realmente populares, como “Snatcher” de Hideo Kojima, y actualmente se siguen publicando muchas novelas visuales. Por algún motivo, las aventuras de texto se suelen basar en menús y las acciones no se suelen introducir directamente con el teclado. ¿Crees que se debe a la complejidad del lenguaje o es por algún motivo cultural?

En realidad, el japonés no es tan complejo como pueda ser el chino. No creo que el lenguaje en sí haya hecho que las aventuras puramente de texto no tengan éxito allí, sino que en los días del apogeo de las aventuras de texto en el resto del mundo los parsers japoneses eran primitivos en comparación con los occidentales y además hay que tener en cuenta el despegue de los gráficos a finales de los ochenta.

Las primeras aventuras conversacionales en Japón usaban katakana para introducir texto y requerían que los jugadores empleasen un japonés “roto” para realizar las acciones.

Creo que funciona bien para juegos basados en verbo y sustantivo, una vez que conoces las normas que el juego espera. En japonés se emplea sustantivo (partícula) verbo, pero en los primeros parsers se omitía la partícula. Los espacios no se usan en japonés para separar las palabras, lo que complica aún más los parsers, ya que muchos esperan un espacio para obtener las palabras de las acciones que introduce el usuario.

Las palabras en japonés se pueden escribir de muchas formas y de distintas maneras, lo que requiere un parser aún más complejo, a no ser que se den instrucciones muy precisas al jugador sobre cómo se espera recibir las acciones. Cuanto menos natural sea la interacción, menos inmersivo es el juego.

Creo que la única razón de que las aventuras occidentales no hayan sido populares en Japón se debe a que es mucho más complicado desarrollar un parser japonés en los sistemas tan limitados que había por aquel entonces. Cuando mejoró el hardware, el género ya no era viable comercialmente en occidente y el mercado simplemente evolucionó.

Los juegos con múltiples opciones, con personajes que hablaban y con cuadros de diálogo funcionaron muy bien en el mercado japonés. Suelen tener pocos puzles y son más clasificables como “ficción interactiva” que como “aventuras conversacionales”.

Mi intención es dar soporte a Adventuron para el japonés, de forma limitada al principio eso sí, ya que es una tarea bastante tediosa. La versión en español de Adventuron se ha ignorado de forma casi completa así que voy a hacer la versión japonesa porque realmente me gusta. Adoro Japón y los juegos japoneses, así que sería un sueño hecho realidad ver el primer juego de ese tipo creado con Adventuron y posiblemente una traducción algo más adelante también. Por otro lado, he estado buscando fuentes con estilo 16 bits para cuando libere la versión japonesa.

Muchas gracias por tu tiempo y mucha suerte con tus proyectos.

Gracias por tus preguntas. Espero que tengas un gran 2020.

English version of the interview

Mark James Hardisty published an article about you in the fifth issue of The Classic Adventurer and you said that Adventuron was created to test if a complex IDE was feasible in the browser. At this point, do you think it has fulfilled your initial purpose or it has to evolve more?

There are many aspects of the editor I’m working on now to make things a lot nicer. It will never be a complex IDE but I think that it largely fulfills the minimal feature set required for this domain of problems.

Last year, the project turned into Adventuron Classroom, a tool “designed to teach kids 8+ to code at the same time as harnessing their natural storytelling abilities”. How many schools have contacted you in order to use Adventuron Classroom as an educational tool?

I’ve contacted many schools, including my old school, and reached out to many teachers but I think as it stands, it’s failed in actually appealing to the target audience.

I also contacted the local library to see if I could host a “learn how to code session” but was told “we feel that its retro look might be interesting to adults as a reminder of how ‘computing’ used to be but up against the slick graphics of today’s gaming world may feel a little old fashioned to children”.

You can’t argue with overwhelming consensus.

My goal in the near future is to add a graphics editor, and to enhance the GUI to downplay the role of the code editor in the early stages of development.

Games created with Adventuron can not only be played in browsers (both desktop and mobile), but you have created utilities so the code can be used in parsers such as PAW or DAAD. What motivated you to create these converters?

I never really wanted Adventuron to be a platform of ports, I wanted it to be a platform of original content. I think I just indulged myself a little too much here because converters are fun.

You’ve used your own tool to create many adventures, including conversions from old classics. Which was the most fun to create? Which one is the most played on itch.io?

“THE PATH” is the most played game I’ve released so far. There are over 6,000 views on the page (plays are not recorded accurately by itch.io presently).

“THE PATH” is an item allocation puzzle with a couple of little twists. I wanted a game that someone with zero knowledge of text adventure conventions could play. I knew I wanted a game without standard movement.

I also observed that most text adventure games involves noun scanning, then the chore of

EXAMINE XXX, then figuring out where to use the objects. What if the puzzle was purely, what to use - and what if you could choose the wrong object in the wrong place? Navigation and item acquisition were completely removed, and the only thing to think of is how to use what you have.The game (appears to be) very simple. The player is presented with a one sentence scenario, and the player must tell the game which item you want to allocate to the problem. Once the item is used, it is lost, and another scenario is presented.

There are 12 scenarios, and they are delivered in pseudo-random order. The randomness was done intentionally, to force the player to not just be able to memorize and tweak their path one variable at a time.

When the path is jumbled, the player must remember their learned wisdom at each step rather than just repeating the exact same commands, which I think would start to feel more like a list writing chore.

“THE PATH” plays mind games with the player which will either result in extreme frustration or possibly obsession and appreciation. As the game was released as free, and experimental, I didn’t mind players believing the game was unfair. The alternative would be to spoil the revelations they would have to come to themselves.

Losing the game and gaining wisdom whilst losing is the core mechanic. It’s extremely unlikely that anyone can complete the game on the first try.

And the latest one is “TWO”, a short and story-less game…

“TWO” was a joy to write just because I put it together so fast, and I really liked the challenge of making a game were all messages were just two words (max).

Those that know me know that I have a bee in my bonnet about how “Interactive Fiction” is actually a non inclusive moniker to represent what I view to be certain types of object-centric “text adventure” games.

I feel it’s gatekeeping when you insist on defining a genre by the word (“fiction”) that does not apply universally to all games in the genre.

Anyway, with a two word limit, “TWO” was necessarily puzzle heavy. I think puzzle heavy games are fun but that’s just like my opinion 😄

“TWO” was purposefully story-less. It has no more narrative than a 2D platform game. And yet on itch, I still had to select the “interactive fiction” category. Gatekeepers be gatekeepers.

Out of curiosity, which are your favourite text adventure games from the eighties?

I absolutely LOVE “The Famous Five”. Also “Robin of Sherwood”, “Rebel Planet”, “Gremlins”, and similar. Oh, and “Valkyrie 17” was a guilty pleasure too. I remember picking that one up in an indoor market in Covent Garden.

Later I got into more text-heavy games such as “The Beast”.

Back then, developing for the first home computers was very different from what is done today. Do you think that developing software nowadays is a better experience thanks to powerful IDEs and webs like Stack Overflow? Or maybe developers were more creative decades ago when the resources were limited in every sense?

Modern development is better? Well it really depends on the person. Everything is a trade-off.

I think that a lot of people that want to write an 8-bit style text adventure don’t just want to write an 8-bit style text adventure. They want to write an 8-bit text adventure, and that involves paying whatever price must be paid to achieve that.

The tools for building REAL 8-bit text adventures (as opposed to Adventuron’s approximation) are getting better all the time.

You still have a lot of issues though with things like screen real estate, speed of streaming graphics, byte limits, distribution, the ability to quickly resume a game, the inability to scale to the device profile, etc. But, on the other hand, it feels genuine, and it’s such a thrill seeing your 8-bit style text adventure running on real hardware (sorry Adventuron).

For those without the purity of a nostalgia requirement, the intention of Adventuron is to provide a really fast development loop. Change something, instantly be able to test it and review it. No setup, just go to the URL.

Adventuron is far less efficient than those older systems. It achieves what they achieved, but flexibility has its price in bytes. That’s another reason I enjoy the converters. I get to say that an Adventuron game fits into a Spectrum (on a technicality).

As I said before, games created with Adventuron can be played both on desktop browsers and mobile browsers. But, in my opinion, playing on a mobile device or even on a tablet it is not as satisfactory as doing it with a computer and keyboard. Do you think this is a problem to attract new players or is it more problematic the fact that people nowadays wants to read less text in games?

I think it really depends on the style of game, the text flow system, and the quality of the shortcuts, as to how well a game plays and flows on mobile.

I think a game like “TWO” is probably more fun to play on mobile. You get haptic feedback from key presses, the commands are short. The text always fits on the screen. The text size is big (25 columns). You can also navigate by touching directions, which is strangely satisfying.

For games with a lot of text, a complex parser, and a lot of noun hunting, I think that mobile play can be exhausting.

Adventuron provides authors with tools for optimizing their layout for mobile. Optimizing layout for mobile involves making sure that the graphics are in letterbox aspect ratio (at least 3:1), not printing vertical object lists, integrating the room header description into the description text itself rather than having a completely separate line.

Optimizing margin spacing, and making sure that large narrative story blocks are delivered one paragraph at a time.

Later versions of Adventuron will better scrolling behaviour and text scaling options. Adventuron can be fun with the right game, but there is much much room for system level improvements for games with a lot of text.

Eight years ago Andrew Plotkin told me that he created some features such as dynamic maps and in-game note taking in order to help the players. Have you thought about incorporating these kind of features on Adventuron Classroom or do you prefer to focus on the development of the parser itself?

I absolutely think that navigation is a huge problem for beginners, and even for experienced players on large maps, so I’ve been developing an in-game mapping (and transport) system, which should make its way into the system sometime in 2020.

It’s a grid based system, and utilizes the game data and the explored area of the game to dynamically make a map.

I personally think that visual UI clutter takes you out of the game, but I also think that with enough configurability you can indeed please all of the people all of the time.

In-game note taking is of course a goal, as is keyboardless play (the latter of which I demo’d to a few people at Play Expo last year).

You have recently created some jams in Itch.io that have sparked the creation of many new adventure games. One of them ("Mushroom Hunt") was even featured in Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Are you happy with the response of the community?

I’m very happy with the response to the jams. I think it’s more fun to do something socially, and pseudo-competitively as well.

The first Adventuron CaveJam was way more popular than I had expected, and I think the key to that was providing a template and some very simple rules.

“Mushroom Hunt” was the breakout hit of the first jam. It’s absolutely beautiful to look at and rightfully garnered a lot of attention but there were some other standouts too. I don’t want to single out any other games because I don’t want to play favourites, but I was very happy with the quality of some of the entries.

The Halloween Jam came soon after and some absolutely amazing games came out of the second jam. I have also been very happy to see some beginners to coding not only take their first steps, but to deliver some very nicely written and designed games too over the course of these jams.

I’ve been spending some time on my other projects, so I’m pulling back from doing more jams until I add a few more useful features to Adventuron and have more time on my hands. I think that just repeating what was done before is boring for me, and boring for participants too. Best to mix things up.

You have lived recently in Japan, a country where a vast amount of text adventures has been published. Some of them are really popular here, such as Hideo Kojima’s “Snatcher”, and nowadays many visual novels are still being created. For some reason, text adventures there are usually menu based and commands are not entered using a keyboard. Do you think that’s because of the complexity of the language or it’s more due to a cultural reason?

Japanese isn’t as complex as Chinese really. I don’t think that the language itself precludes text adventure games being successful there, but there were implementation and timing issues in the heyday of parser based text adventure games which kind of means that Japan’s parser-game technology was still primitive compared to western tools at the point that the graphics arms race was taking off globally in the late 80s.

Early parser based text adventures in Japan used katakana inputs and required that players type broken Japanese to enter commands.

I think it works well for verb noun type games, once you know the rules of what the game is expecting. In Japanese it’s noun (particle) verb, but the early parsers omitted the particle. Spaces are not used in Japanese to separate words, which makes things tough for would-be parsers as most parsers expect a space to tokenize their words.

Words in Japanese can be written in many forms, and in many different ways, which requires a much more powerful parser, or strict instructions to the player on the way they are expected to communicate with the parser. The more unnatural you make the interaction, the less immersive the command entry is.

I think the only reason that western style text adventures were not popular in Japan is that it was more clumsy to write a good Japanese parser in a minimal amount of bytes at the time then genre was popular. By the time the hardware improved, the genre was finished commercially in the west and I just think the market had moved on.

The style of game with multiple choice and reams of talking heads and dialog boxes just struck a chord with the Japanese market. I think those types of games are puzzle-light, and they are absolutely better classed as “interactive fiction” rather than “text adventure”.

Adventuron will absolutely support Japanese in the future, albeit in a limited form at first, and it’s very much a back-burner task. The Spanish version of Adventuron has been almost completely ignored, so I’ll be doing the Japanese version as a labour of love. I love Japan and Japanese games, so it would be a dream come true to see the first Japanese game on Adventuron, and then possibly to see a translation at a later date too. I’ve been looking at some good 16-bit style fonts for the Japanese release too.

Thanks a lot for your time and good luck with your projects.

Thanks for your questions. Hope you have a great 2020.